As the specter of affirmative action has returned to haunt American political discourse in the wake of the Students for Fair Admissions rulings that were recently handed down from the Supreme Court, a peculiar talking point has reemerged from its hibernation. “Affirmative action primarily benefits white women,” say a bunch of Twitter accounts and articles in respected media sources, more or less in unison. I’ve helpfully provided a few choice examples in the collage above.

If white women are, in fact, the primary beneficiaries of affirmative action programs, then what is the intended conclusion we should draw? Does it prove that affirmative action is ultimately yet another handout to the white majority, or does it serve to indict white women as advocates against their best interests, as noted male feminist and white anti-racist Tim Wise insists in his 1998 paper “Is Sisterhood Conditional”?

These questions can, should, and must be grappled with, but what has to take primacy in this discussion is the fact that the central claim is essentially false. Put simply, none of the sources these writers and tweeters cite prove that white women are the primary or disproportionate beneficiaries of affirmative action.

The history and evolution of this claim demonstrates how the internet can easily play host to a game of epistemological telephone, distorting the truth with every step away from original sources. So, with that in mind, let’s trace some origins.

The Crenshaw Paper

Olayemi Olurin, when pressed on evidence for the claim in her tweet above, cited a long and accusatory article in that respected reporter of current events known as Teen Vogue. Despite a title that claims “Affirmative Action Benefits White Women Most,” though, the only concrete evidence it marshals is a single link.

Similarly, A Vox story from 2016 blares the headline “White women benefit most from affirmative action — and are among its fiercest opponents." The article is long and rambling, with dozens of hyperlinks in the text to other articles, studies, and court rulings. It too, though, dedicates only a single sentence to back up its titular claim that “white women benefit most from affirmative action.” Here it is, in full:

The battle to erase race from the application review process for admission comes with an interesting paradox: "The primary beneficiaries of affirmative action have been Euro-American women," wrote Columbia University law professor Kimberlé Crenshaw for the University of Michigan Law Review in 2006.

Crenshaw’s paper also just so happens to be the singular source deployed by Teen Vogue.

While both Vox and Teen Vogue accept Crenshaw’s claim on faith, reading the paper itself doesn’t bring us any closer to hard evidence. The 2006 paper, despite being published in a law review journal, doesn’t contain a single citation, and the context of the excerpted sentence provides no further clarity. After commenting on an issue of Newsweek that discussed affirmative action while largely neglecting its gender-based variant, Crenshaw states

This is simply a gross distortion of reality, given that the primary beneficiaries of affirmative action have been Euro-American women.

And with that sentence, we come to the end of our trail. Is that all there is? An evidentiary dead end? Shockingly, yes. The lack of a sound evidence base in these articles has correspondingly been noted by others before. So why did I even go through the effort to write this piece in the first place?

Well, there is one article that bravely makes the effort to find some actual sources for its claims, obviously a nigh-insurmountable task for many of our valiant but overworked journalist friends.

In “Affirmative Action Helps White Women More Than Anyone,” TIME magazine writer Sally Kohn thankfully eschews citing the Crenshaw paper for a few sources of greater substance. Its first link directs readers to an article in The Chronicle of Higher Education written by Michele Goodwin. The relevant excerpt from the piece:

Women were (and continue to be) primary beneficiaries of affirmative action and civil rights laws

There’s no hard evidence provided for the claim here either. Hmm… not much better than Crenshaw. Can we do better?

The Blumrosen Report

Kohn’s second source refers to a study from 1995 that purportedly found that “6 million women, the majority of whom were white, had jobs they wouldn’t have otherwise held but for affirmative action.” Clicking the link first took me to the “Is Sisterhood Conditional?” essay written by Tim Wise that I briefly quoted earlier. Wise’s essay draws the “6 million women” claim from a 1997 book by Ellis Cose, titled “Color-Blind: Seeing Beyond Race in a Race Obsessed World.” I found a copy of the book on Internet Archive, which on page 171 cites a report from Working Woman magazine, that in turn quotes a “1995 study by Alfred Blumrosen, a professor at Rutgers University Law School and consultant to the Labor Department” which stated (according to the Working Woman excerpt) that an

Estimated six million women wouldn’t have the jobs that they have today were it not for the inroads made by affirmative action.

The Blumrosen study, I came to realize, also serves as an (unsourced) second piece of evidence in the Vox piece, which refers to “a 1995 report by the Department of Labor” that found “6 million women overall had advantages at their job that would not have been possible without affirmative action.” Further, it’s cited in a recent USA Today piece1 claiming in its headline that “white women benefit most from affirmative action,” and citing “a Labor Department report in 1995” that found "affirmative action helped 5 million members of minority groups and 6 million women move up in the workplace.”

You’d think that my search would be over now that I was blessed with the name of the study’s author and date of publication, but no. The only sources from 1995 that I could find were second-hand coverage of the study in newspapers, including the New York Times and The Washington Post. But I was determined to read the study itself.

So I teamed up with a friend to trawl the internet, searching for the “Draft Report on Reverse Discrimination” written by Alfred Blumrosen and published in the August 1st, 1995 installment of the Daily Labor Report (confusingly not an official government periodical). Around an hour of searching later, he finally found the original document (thanks to @danielhcshaw for the help).

The Blumrosen Report’s main subject, as its title suggests, is the question of whether affirmative action resulted in systemic reverse discrimination against whites and males. Blumrosen finds that it didn’t, determining claims of reverse discrimination in the courts to be few and generally without merit, and concluding that there was “no widespread abuse of affirmative action programs in employment.”

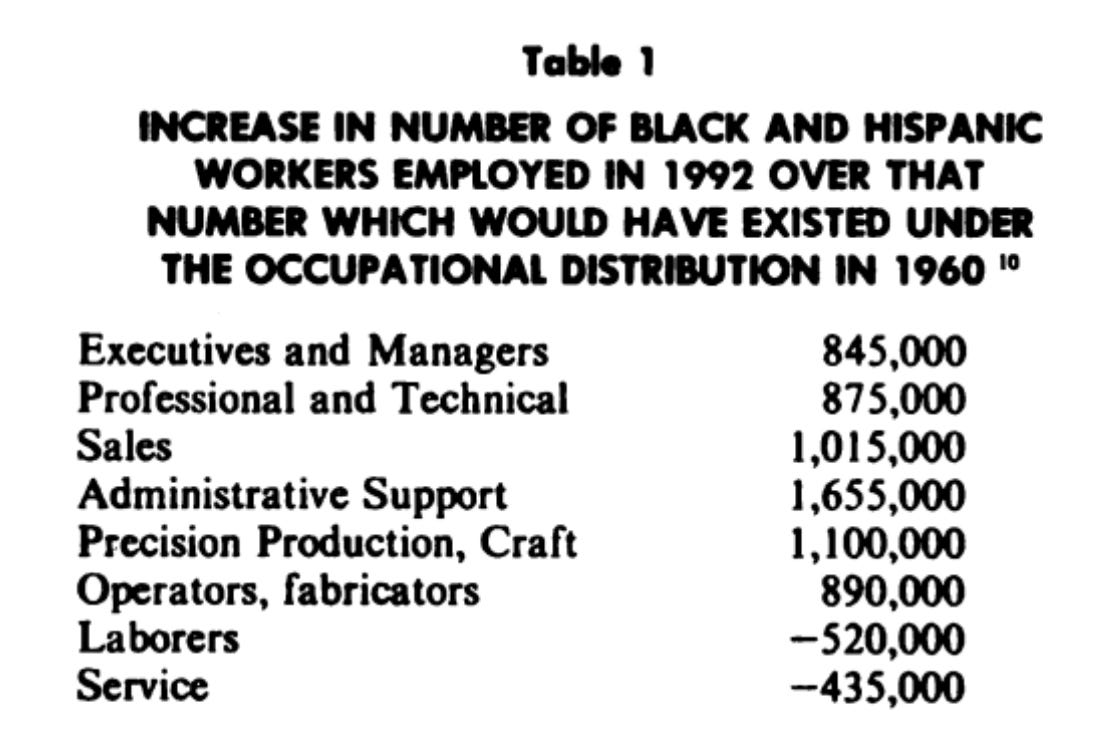

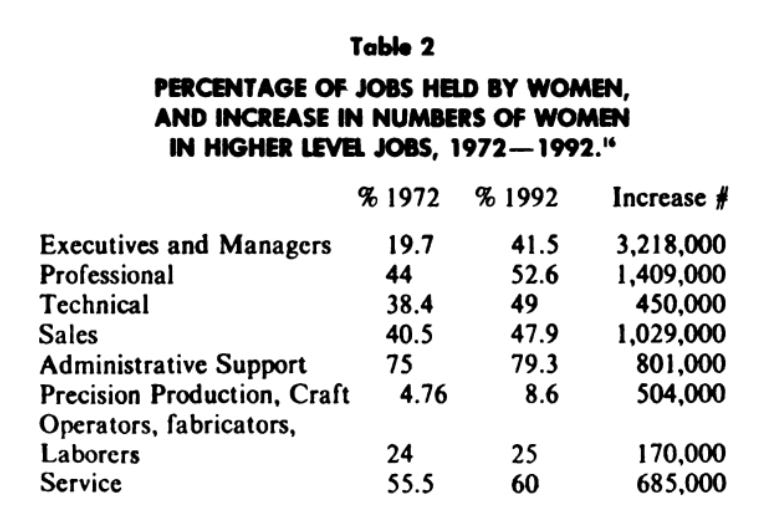

However, Appendix A of the report also contains an analysis (excerpted from another paper, one of Blumrosen’s own that was delivered at a 1994 conference, which in turn cites Blumrosen’s 1993 book Modern Law for the methodology) of the changes in job classification among women and minorities over the decades leading up to 1992. In Appendix A’s Tables 1 and 2, we may find where the much-referenced statistics originated.

While Blumrosen attributes some of the gains made among black and Hispanic workers to affirmative action in the text of the Appendix2, there is no strictly methodological reason for this to be true. He did not claim to be assessing the impact of affirmative action policies in particular; he merely estimated the sectoral shifts in the employment of women and minorities, gesturing towards affirmative action as a driver of the shifts. The titles of the tables betray as much: they are analyses of demographics, not causality. And besides: Blumrosen didn’t even mention affirmative action in his discussion of gains made by women!

So, why have recent sources misinterpreted Blumrosen’s work? Their errors probably originated with missteps in the contemporary news coverage I cited earlier, which is evidently much easier to read than the primary source itself. The ultimate blame might rest at the feet of the Times, which reported on Blumrosen’s work in an arguably deceptive manner, writing that “affirmative action had helped five million members of minorities and six million women move up in the workplace.” While not technically incorrect, the phrasing is easy to misconstrue — sufficiently enough to defeat the fact-checkers at Vox, TIME, and USA Today.

Contractors and IBM

Unfortunately for my word count, there are still a few more citations in Kohn’s TIME piece that I need to address. Firstly,

Another study shows that women made greater gains in employment at companies that do business with the federal government, which are therefore subject to federal affirmative-action requirements, than in other companies — with female employment rising 15.2% at federal contractors but only 2.2% elsewhere. And the women working for federal-contractor companies also held higher positions and were paid better.

The link directs readers to a fact sheet published by the National Women’s Law Center, and seems to reference footnote 40 in the document. The footnote leads to a 1984 document published by the Citizens’ Commission on Civil Rights, a defunct progressive organization. The document cites an “unreleased study conducted by the OFCCP [Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs] in 1983” which backs up Kohn’s claims. Further, the document states that

For non-contracting companies, minority employment increased 12.3% and female employment 2.2% with an 8.2% growth in total employment over the same period.

So, if we are to accept the (unpublished) statistics from the OFCCP, we have finally found an actual instance of women arguably benefitting more than minorities from affirmative action! Unfortunately, it’s 43 years out of date.

Continuing on with Kohn’s article,

Even in the private sector, the advancements of white women eclipse those of people of color. After IBM established its own affirmative-action program, the numbers of women in management positions more than tripled in less than 10 years. Data from subsequent years show that the number of executives of color at IBM also grew, but not nearly at the same rate.

This paragraph strangely compares the rates of employment growth for two demographic groups over two distinct time periods. I don’t think I need to elaborate on why this is a grossly inappropriate methodology!

It also cites two separate sources for its figures. The first link references the same Citizens’ Commission on Civil Rights document, while the other links to a dated fact sheet from Americans For A Fair Chance, a pro-affirmative action advocacy group. Why use two sources from two time periods for your evidence? Because if Kohn used only one source, it wouldn’t help her point.

From the Citizens’ Commission study:

Black employees at IBM increased from 780 in 1962, to 7,251 in 1968, to 16,546 in 1980. While in 1971 IBM had 429 black, 83 Hispanic and 471 female officials and managers, by 1980 the numbers had risen to 1,596, 436 and 2,350, respectively. From a situation of token representation (1.5% minority and 12.7% female employees) in 1962, IBM has moved to significant integration of its workforce (13.7% minority and 22.2% female employees).

Clearly, affirmative action policy at IBM had a drastic impact on the representation of both women and minorities. Women’s representation in managerial positions increased at a rate slightly higher than that of black employees and slightly lower than Hispanic employees during the period studied (4.99 times as compared to 3.72 and 5.25 times, respectively). In the overall workforce figures, though, minorities benefitted far more than women did.

The Americans For A Fair Chance fact sheet that Kohn compares these figures with states that “from January 1996 to March 2001, the percentage of minority executives [at IBM] increased 170 percent.” So, rather than addressing the nuanced truth about the impact of IBM’s affirmative action program, Kohn compared apples to oranges. She even got her math strangely garbled in a way that hurt her argument — characterizing female representation in IBM management as “more than trip[ling]” when it increased by nearly a factor of five! Technically she’s not wrong, I guess?

On an unrelated note, the Americans for a Fair Chance fact sheet Kohn references has only one citation to back up its claim that “affirmative action programs have opened up job opportunities for qualified women to achieve higher wages, advance in the workplace, and seek nontraditional careers that make them better able to meet the financial needs of their families.” Would you believe me if I told you it referenced a study by a certain Blumrosen?

In sum, Kohn’s article, like all the others, was written to a wholly negligent factual standard, though apparently still good enough to be cited in the New York Times.

The Truth of the Matter

The academic research assessing the impact of gender-based affirmative action has come to no certain conclusion about its impact on white women’s employment and hierarchical elevation in the workplace vis-à-vis that of minority populations.

One of the most cited studies in the literature is from 1989. The paper analyzes the effect of affirmative action requirements in federal contracts, concluding that “affirmative action has contributed negligibly to women’s progress in the workplace,” and “has in some circumstances hindered the advancement of white females” while “black females have fared significantly better than have white females under affirmative action.”

A more recent study of Florida firms in 2006 (thanks to @MayaBodnick on Twitter for bringing it to my attention) similarly finds that employer support for affirmative action doesn’t predict white female employment at unskilled, skilled, or professional levels. A study from 2015 also finds that “affirmative action increased the employment of black and Native American women at the expense of white women,” though the effect becomes positive “from the 1990s onward.”

In contrast, a 2012 study by the same author as the 2015 paper finds that federal contracting requirements did have a positive impact on female employment in “high-paying skilled occupations.” In fact, the paper suggests that the most powerful impact was on the employment of white women, with significant but smaller effects on the professional employment share of black and Hispanic women and black men.

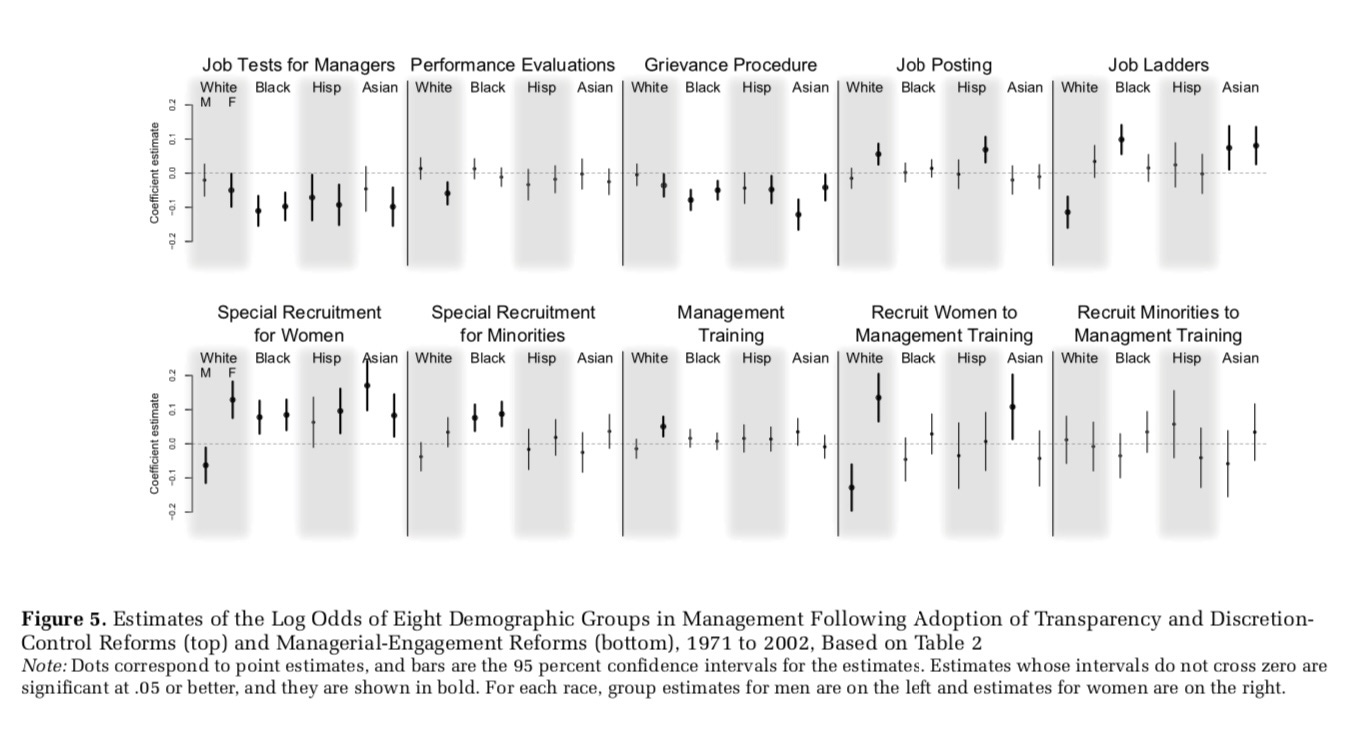

Other studies have come to more ambiguous conclusions. A 2006 study determined that the adoption of affirmative action plans or diversity programs was more strongly associated with the share of white women in management positions than black women or men, but a number of individual reforms had larger effects for black women and men. Finally, a 2015 study by several of the same researchers found that reforms intended to increase general diversity had varying effects on underrepresented groups, though reforms explicitly intended to benefit women tended to help white women most.

This is only a brief sample of the literature, so I won’t draw any firm conclusions here — that’s a job for someone far more skilled in the art of meta-analysis than I — but my sample proves equivocal on the question of whether the causal impact of gender-based affirmative action (on a firm-by-firm or government policy level) has been greater than that of race-based programs in certain instances.

While gender-based affirmative action in federal contracts still exists, it also doesn’t seem to be talked about much anymore, and I can’t find much information on its scale today. Extant gender-based affirmative action is seemingly largely on the level of executive suites and corporate boards, and perhaps covertly on some graduate school admissions committees, but putting a strong emphasis on gender-based government quotas and contracting regulations may be anachronistic, as Matt Yglesias has noted.

It’s also important to keep in mind one of the fallacies that a lot of the coverage of this issue falls victim to: just because the share of women in selective positions has increased more than the equivalent share of minorities doesn’t mean that the difference is due to the impact of affirmative action. Increased female presence in professional and academic spheres has a multitude of social and economic drivers beyond targeted policy.

This is especially true for college admissions. Female students in 2020 made up a full 58 percent of currently enrolled undergraduates, and women have composed the majority of undergraduates since the 1970s. This is not the product of a conscious policy choice by legislators or administrators to admit more women than men. In fact, some selective schools now have higher admissions rates for men to make up for that gap, which perhaps serves as a tacit form of affirmative action itself.

Essentially, the part of the “primarily benefits white women” claim that might be true is ultimately irrelevant to the debate over contemporary college admissions practices, and perhaps irrelevant in the labor market at large as we find ourselves over two decades into the 21st century.

Conclusion

As I noted earlier, I’m not entirely sure what substantiative point affirmative action defenders who bring up the White Woman Take are trying to make, other than a critique of white women for being insufficiently supportive of race-based affirmative action in dereliction of their supposed solidaristic duty.

As a result of that ambiguity, the claim has naturally been co-opted by unintended parties. Most hilariously, it found its way into an amicus curiae brief in the Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina case — on the side of the plaintiffs! The Liberty Justice Center, a conservative organization, cited Crenshaw’s paper (as well as the Vox and TIME articles) to argue that affirmative action is an improperly-targeted intervention. Ironic.

The moral of the story, if there must be one, is that the average columnist or Twitter commentator should not be trusted to conduct proper research. A case could be made that women benefit most from certain affirmative action programs, if any writer might be competent enough to scan the academic literature. But not one has decided to take that step. Instead, they’ve resorted to low-quality sources and logically shaky assertions of fact, mindlessly parroting Crenshaw and Blumrosen without examining their own biases.

If white women have benefitted disproportionately from affirmative action — which is admittedly possible, albeit only outside of undergraduate admissions — not one of that claim’s prominent advocates on Twitter or in the media has demonstrated the requisite familiarity with the sources necessary to back up their claims.

But if white women haven’t benefitted disproportionately from affirmative action, well… then they’re all wrong. And being wrong speaks for itself, doesn’t it?

The USA Today article links directly to the 1995 New York Times story on the report I mention in the following paragraph, which would have saved me quite a bit of effort if I knew so initially.

“Affirmative action apparently continued through the Reagan-Bush period of intense opposition to affirmative action and broad interpretation of the statute. The net increase in jobs between 1983 and 1992 was 16,764,000. The net increase in jobs held by black and hispanic [sic] workers during that period was 5,976,000… this tends to confirm my suggestion based on earlier statistics that, ‘affirmative action has developed deep roots in the industrial relations system.’”

Interesting, I did not know this theory was taken seriously. But I suspect that once affirmative action became law, the corporations no doubt followed suit, even more so. When I recently worked for a Fortune 500 company, minority recruitment was taken very seriously.