I. The Failed Models

Elon Musk is running a command economy. That’s right, I said it. I finally said what you all were afraid to say.

Put someone in charge of the economy, without the millions of checks and balances on their power that the market provides, and they’ll do dumb stuff. It’s an inevitability. If they’re smart, they’ll merely impede economic growth by accidentally directing too much capital to the iron industry and too little towards cultivating fresh fruits. If they’re actually stupid, God help us all.

There’s no shortage of scholarship on the subject of how centralized authorities fail to make the best decisions, even if they are perfectly well-intentioned and highly knowledgeable. Most notably, the libertarian economists Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich von Hayek first formalized this notion around a century ago, in one of those few cases where I unfortunately just have to hand it to the Austrian School. In their conception, the failure of central planning is attributable not to malevolence, foolishness, or counter-revolutionary wreckers among the planners, but to the inherent impossibility of the Soviet economic project. No matter how hard a planner tries, they cannot capture the highly complex information on the preferences of individuals and firms that can only be truthfully expressed by the act of transaction itself — the revealed preferences of economic actors.

Such a notion might seem so obvious as to be unremarkable today, but it was genuinely far-sighted at the time. The debate over the economic calculation problem, as it came to be called, raged throughout much of the previous century, and to a lesser extent still continues today among the plebians, at least if Google autocorrecting my search to “economic calculation problem debunked” is any indication.1 Mises and Hayek came up with their critique of central planning at a time when the Soviet economy was young, and critiques of the USSR were focused more on freedom than economic viability. Uncertainty about the capacity of the Soviet economic system wasn’t just restricted to the period before World War II, though.

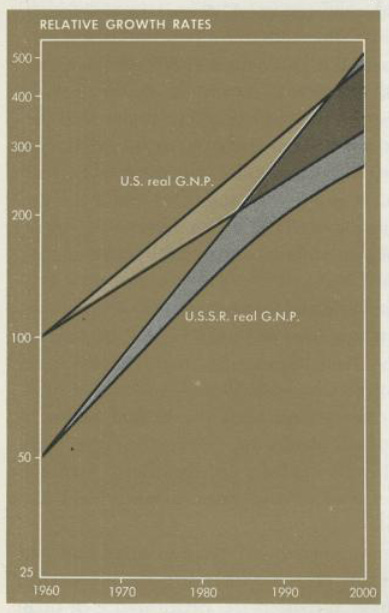

One of the strangest aspects of midcentury American political economy was that, as late as the 1980s, several mainstream economics textbooks predicted that the economy of the USSR would surpass that of the USA at some (constantly shifting) point in the future. There was no acknowledgement of any inherent flaw or fundamental inferiority of Soviet central planning that would inhibit this growth. The most well-known examples of these charts were in textbooks written by none other than Paul Samuelson, whose New York Times obituary referred to him humbly as “the foremost academic economist of the 20th century.”

Of course, this was by no means a universal opinion. In a declassified CIA document from 1984, analysts predicted that the gap between the performance of the Soviet economy and the American economy that had begun to widen around 1975 would continue to broaden as the decade progressed. “There is little reason to expect Soviet growth to exceed that of the United States on average during the rest of the decade,” the report stated, which frankly seems pretty hedged in retrospect.

Nevertheless, these modeling errors in textbooks were notable. As a 2009 paper analyzing textbook predictions of Soviet growth by David Levy and Sandra Pert states, “what we find repeatedly is over-confidence in the potential for Soviet growth and an asymmetric response to previous forecast errors.” The failed projections, they further found, weren’t due to the ideological bias of authors, but simply a failure to understand the nature of the USSR’s institutions. Many economists to the left of Samuelson didn’t make his mistakes; in fact, their distrust of simple economic models kept them from the same errors.

“We are all constrained by means of models: we gain insight in one dimension by blinding ourselves to events in other dimensions,” Levy and Pert say. Foolish is the man who has a one-dimensional view of what makes the economy tick.

It’s also true, though, that a good portion of the blame can be placed on the unreliability of the statistics coming out of opaque Soviet institutions, and not just the methodological errors of American economists. According to a 1992 paper, the “view held widely” in the 1950s was that “Soviet central planning would produce persistently high growth rates into the foreseeable future.” But even contemporary criticisms of those views were insufficiently harsh, say the authors: “indeed, criticisms of Soviet statistics that may have been viewed with skepticism then [1962] are now seen to be unduly mild… the deficiencies in Soviet statistics [were] symptomatic of deep systemic problems in the Soviet economic system.”

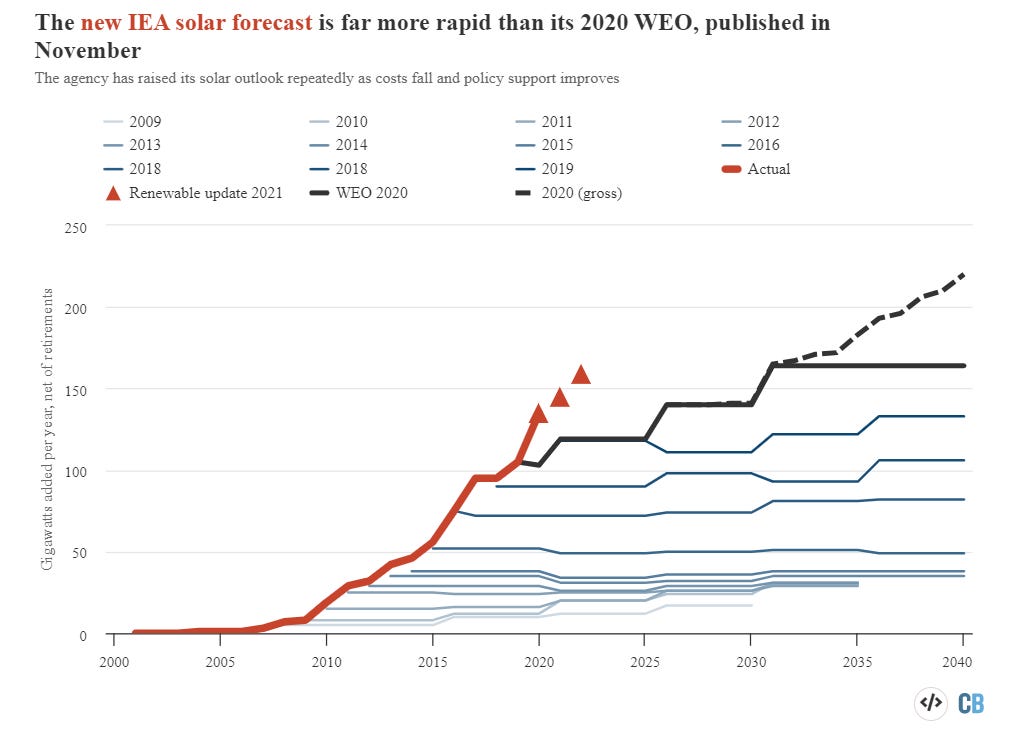

In conclusion, economic forecasts are fallible, just like central planning. Or at least the forecasts of last century were fallible; perhaps we can extrapolate that conclusion to today’s forecasts. Who knows.

II. The Towers of Babel

We’re primed to think of central planning as a left-wing concept, and it has a powerful association in American cultural memory with the policies of the former Soviet Union. However, there’s nothing about economic centralization that necessarily has to be socialist, or even left-of-center. Consider, as an example, the oil-drunk sheikhs of Saudi Arabia.

When they’re not busy dismembering journalists, Saudi Thought Leaders compete to imagine the most garish, impractical, and generally ill-thought-out engineering feats that they can drain the state’s coffers with. On paper, there’s a sound economic explanation for this: the forward-thinking Saudis know that the unique advantage they hold as an oil producing powerhouse will soon come to an end in the era of green energy, so they’re working to transition the state towards endeavors that can endure after their oil wells are no longer economically relevant. But in practice, it’s clear that these megaprojects cater more to the whims and fancies of Saudi rulers, with little consideration for fiscal feasibility.

Take The Line, which in a more sensible country would start and end as concept art that an architect draws in his free time. The project entails constructing a dense and car-free 170 kilometer long and 500 meter tall structure stretching through the desert, which Crown Prince (and Jeff Bezos bestie) Mohammed bin Salman claims will be inhabited by nine million people in “carbon-positive urban developments powered by 100% clean energy.”

According to Nadhim al-Nasir, the CEO of NEOM2, the project is already one-fifth complete. But unsurprisingly, outside observers have cast doubt on the feasibility of The Line, beyond mere criticisms of its reliance on surveillance, environmental impact, abuse of migrant workers, and the displacement of a local tribe. The project “looks like a total fantasy,” says Archinect. “Robot maids, flying taxis, and a giant artificial moon headline as features of a promised tech paradise,” says CNN, incredulously.

Alternatively, “THE LINE is a civilizational revolution that puts humans first, providing an unprecedented urban living experience while preserving the surrounding nature. It redefines the concept of urban development and what cities of the future should look like,” or at least that’s what the project’s website gushingly claims. Ironically, most of the jobs created by these Saudi proposals are probably for the type of fresh-out-of-college McKinsey consultants who likely wrote this blurb.

The best thing I can say about The Line is that if they somehow pull it off, it will frankly look pretty cool, but I’d bet that the greatest legacy of the project will be a strangely-shaped hole in the Saudi desert, considering the country can’t even manage to complete a single building with a high international profile.

Demonstrating an admirable commitment to complete dominance of the shape-based megastructure category, MBS also recently introduced a proposal to construct a 400-by-400-by-400-meter cube-shaped megalith in the middle of Riyadh. Guess what they’re calling it. Guess. Yeah, they’re calling it “The Cube.”

I think that building a giant golden replica of your religion’s holiest relic to boost your GDP is kind of sacrilege, but as a Jew I’m really not one to judge.

While Saudi projects are particularly outlandish, they aren’t one-of-a-kind. Polities ranging from the autocratic to the democratic build megaprojects for all sorts of reasons. Some are meant to be new capitals, and many are intended to attract new capital. The most ridiculous projects tend to come from countries with little democratic accountability, where rulers are more concerned about making their economies appear powerful than actually improving economic conditions to win popular support, though absurd builds can also come from “benevolent” autocrats who genuinely want to grow their economies but prefer that everything be just a bit more bejeweled than is necessary.

Megaprojects, especially those conceived under authoritarian regimes, rarely end up looking as they were promised back when flashy visualizations and astounding economic figures were first presented to the press. If they’re ever actually completed, it’s inevitably years behind schedule and countless dollars over budget, but many of them end up sitting abandoned, partially-built, as economic reality catches up to unrealistic visions.

Dubai’s 2000s building boom serves as a testament to classic megaproject folly — a glut of farcical projects started during an oil-driven frenzy that was abruptly cut short by the 2008 financial crisis. The repercussions can still be felt and seen today in Dubai, with “mistakes on the lake” so large that they’re visible from space. And sure, private capital has played a foundational role in these projects, but they were ultimately built under the orders of a sheikh, like the famous palm islands and Earth-shaped archipelago.

Even when they’re built with the best of intentions, megaprojects keep falling short. Why? Because they are functionally built to shape the economy rather than to respond to the demands of the market. Massive cubes, palm-shaped islands, and hundred-story pyramid hotels rarely show up outside of autocracies, because only an unaccountable leader would be both stupid and powerful enough to think that such projects are economically sound. And the Middle Eastern petrostates provide a particularly fertile ground for megaprojects: their rulers are autocratic, wealthy beyond belief, and just forward-thinking enough as to know not to fall victim to the resource curse. It’s a perfect storm for some of the most ill-fated construction projects this side of the Tower of Babel.

This is how centrally-planned Arab megaprojects end up telling the same story as those American textbooks that forecasted high Soviet economic growth: economic centralization, and the analysis of such, even when led by those with superficially decent priorities, is still vulnerable to human imperfection and incomplete knowledge. Sometimes, in both America and Saudi Arabia, even diehard capitalists can be fooled by the bluster.

III. The Landed Gentry

I write this at a time of unprecedented crisis for the mercurial kings of social media. Reddit is in the midst of great strife, as the “landed gentry” of subreddit moderators clash with the site’s owners over a proposal to restrict the ability of third-party apps to access its API. Changes to the Discord username system have likewise greatly frustrated users.

But Twitter, perhaps most disquietingly of them all, is lurching unpredictably in an attempt to meet the lofty and peculiar ambitions of its owner. Elon Musk, the maverick billionaire and eternal adolescent, may have finally formally stepped down from his chaotic tenure as Twitter CEO, but he still seems to be orchestrating major business decisions behind the scenes, at least if their blatant idiocy is any indication.

His most recent gambit is perhaps the stupidest yet, and hopefully it will be intercepted by some level-headed hero in the Twitter administrative hierarchy before it’s pushed to the public. Musk wants to restrict the ability of users who don’t follow each other to send direct messages and create group chats unless they are paying for Twitter Blue, ostensibly to reduce spam from bots (for a while now, his favorite windmill to tilt at) that clog DM requests, but his real motivation is to nudge users to shell out eight dollars a month for Blue’s premium service model.

From journalists to artists to run-of-the-mill DM sliders, open direct messaging is an important part of the Twitter experience for many users, and Musk hopes to wring this fact out for a quick buck. This is clear for two reasons. First, there is a preexisting option to restrict all non-follower DM requests, making this change completely redundant. Second, many bad decisions that Musk has made in recent months have been straightforwardly intended to boost Twitter Blue subscriptions, which, as of last indication, didn’t seem to be meeting revenue expectations, casting doubt on his passion project.

Ad revenue on Twitter has plunged by 59% since Musk’s takeover, imperiling the website’s entire business model, which can be attributed to nothing but his own shoddy and impulsive decision-making. “Unpredictable and chaotic” is how one advertising executive described Twitter in the New York Times article linked above, which could just as easily refer to Musk’s leadership style in particular. Only time will tell whether Musk (and Twitter’s new CEO, Linda Yaccarino) will manage to construct a new business model out of the ashes of the old.

In contrast to Musk’s avoidable self-miring in his own proverbial muck, the reason why Reddit moderators and (a selection of) users have come into conflict recently is readily understandable. Reddit has been around for nearly two decades, but it’s still not a profitable enterprise. CEO Steve Huffman said as much: “we’ll continue to be profit-driven until profits arrive.” We’re at a lean time in the tech industry right now, and Musk’s mass layoffs of the Twitter workforce have proven to many other CEOs in the sector that a large portion of their employees are essentially redundant. It’s high time to cut corners.

Reddit decided to cut free API access for large third-party apps, which allows users to browse the website’s content without using its native interface, mostly in an attempt to recoup lost ad revenue. But in an unprecedented act of protest earlier this month, the moderators of many of the website’s largest subreddits resisted by setting their domains to “private,” completely cutting off access to millions of daily users and crippling the site’s usability.

It has been a while since the loudest noise of the protest has died down, but the Reddit Rebellion yet continues. Sure, the users involved are taking it a bit too seriously; Redditors are wont to be at least a little embarrassing in all situations. But it’s still remarkable to see a sort of virtual collective action in practice that could never be accomplished on a platform like Twitter, even if it’ll probably be all for naught.

Whether Reddit will ever find profitability, even if the moderator revolt is successfully suppressed, remains an open question.

IV. The Theory of Vibes

As we’ve explored here, companies operating under capitalism can still be resistant to market forces in the short term, if the right circumstances present themselves. An unaccountable owner can make as many bad decisions as a Saudi sheikh, if he so desires, before he’s driven out of leadership or his firm is driven to the ground.

Philosopher Elizabeth Anderson said something similar but from a different perspective in her aptly-titled book Private Governments — the non-democratically structured firm (that is, almost every business in America) functionally operates as a miniature authoritarian government during the workday. When there’s no accountability from above or below, the pettiest bourgeoisie tyrant can run his firm into the ground to his heart’s desire.

For most firms, this ultimately doesn’t present much of a problem. Even if an owner is irrationally resistant to success, winners win and losers lose. The marketplace churns, and creative destruction works its magic. There is little lost when a product is crowded out by its superior. But social networks are different: they thrive on the cultivation of close ties between users that can’t easily be transferred elsewhere if circumstances necessitate such a move. A social media owner does not merely possess a business. They own a peculiar facilitator of relationships, which can be just as vital and meaningful as it is vile and loathsome.

Elon Musk didn’t buy Twitter because he thought it was making a mistake with its old business model. He bought it firstly because he was forced to, and secondly because of an ideological imperative to secure free speech.3 He certainly does have an idea of how to bring in more revenue, but it’s not very well-reasoned, and you wouldn’t expect it to be. As the mystique of the erstwhile rocket man’s glamorous persona has worn off, some reporting has suggested that Musk may be less of a Renaissance Man and more of a man who has been coasting off of a few lucky business decisions for several decades at this point.

Musk ran Twitter (and continues to do so in a different capacity) essentially off of vibes, like how a Saudi sheikh might decide which implausible skyscraper to erect next. He has turned one of the world’s foremost social media networks into his personal megaproject, and gleefully careens it towards disaster. We can only wish for mere imperfection, which Yaccarino may or may not have the ability to deliver.

But even those companies such as Reddit which do indeed follow profits wherever they may lead can find themselves painted into a corner. Like the modelers who were so confident in their simple pictures of Soviet economic life, relying on unspoken assumptions from across the world, these firms search for an extra dollar in every nook and cranny till all unrealized gains are squeezed dry like a sink sponge, while neglecting the greater picture: it’s far easier to kill by a thousand cuts than to save.

Certainty is a dunce’s game.

Serious post-Soviet collapse socialists have either given up on the traditional notion of the planned economy or (considerably more tendentiously) placed their hopes in the possibility that the calculations of a forthcoming “big computer” will hypothetically tie up the loose ends of economic planning. Less serious socialists somehow do much worse.

The Saudi SEZ (Special Economic Zone) and smart city that includes The Line, as well as several other notably ambitious megaprojects.

Which I would find admirable enough as a free speech absolutist myself, if only it didn’t turn out that Musk’s rule was even more arbitrary than the ancien régime’s. Am I seeing another historical parallel here?

Rip to those soviet central planners but I'm different

Good theory, but I'm pretty sure I could plan the economy without anything going wrong